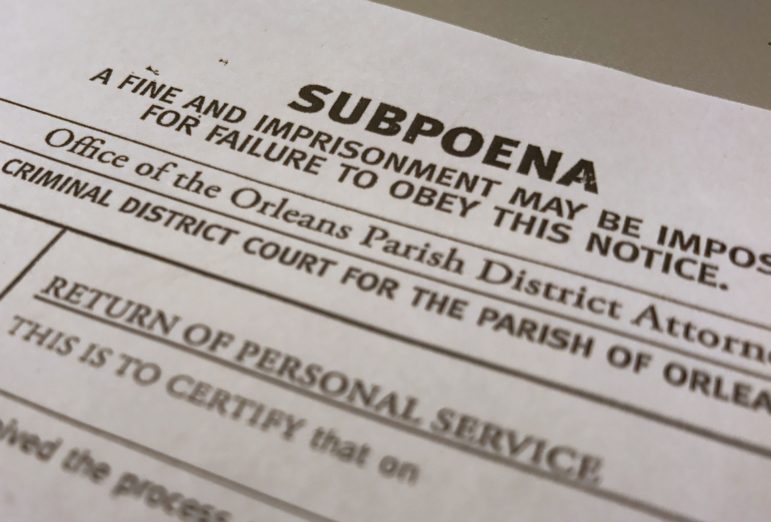

The Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center is suing Orleans Parish District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro over his refusal to hand over so-called “DA subpoenas,” including an unknown number of fake subpoenas sent to witnesses in criminal cases.

The group has asked a judge to order Cannizzaro to turn over the subpoenas and to penalize him for violating the state Public Records Act.

A spokesman for Cannizzaro did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The suit, filed in Orleans Parish Civil District Court on Friday, stems from a May 2015 public records request submitted by Emily Washington, an attorney for the MacArthur Justice Center. She asked for records of requests for DA subpoenas made to judges, as well as the subpoenas themselves, dating back to 2013.

The MacArthur Justice Center also represents inmate plaintiffs in a federal lawsuit over conditions in the city jail.

”Now we learn that there has been a serious abuse of authority related to exactly the subpoenas we sought.”—MacArthur lawsuit

Assistant District Attorney Scott Vincent denied the request because it would require a manual “review of literally thousands of closed files, a substantial number of which are stored off-site.” That’s exactly what the office told The Lens when it denied our recent public records request.

Vincent directed Washington to the Clerk of Criminal District Court, which he said is the “proper custodian of these records.”

However, through The Lens’ recent reporting, the MacArthur Justice Center now knows the clerk doesn’t have all those subpoenas.

Until last month, Orleans Parish prosecutors sometimes issued fake subpoenas to pressure witnesses into private interviews.

Prosecutors are allowed to interview witnesses in private. But first, they’re required under state law — Article 66 of the state Code of Criminal Procedure — to ask a judge in writing and explain why they need to speak with the person. If the judge approves the request, the Clerk of Court issues the subpoena.

Have you received one of these fake subpoenas? We want to talk to you. Email editor@thelensnola.org, or call or text 504-229-2346.

In some cases — the DA’s office can’t say how often — prosecutors didn’t ask a judge and just sent the subpoenas out themselves. The documents were labeled “SUBPOENA” and threatened jail or fines if the person ignored them.

Because the documents weren’t real subpoenas, those were empty threats. The documents don’t appear in court records for the same reason.

“Due to recent reporting by investigative online media outlet The Lens, Plaintiff has now learned that the District Attorney’s response directing her to contact the court for records was knowingly false and intentionally misleading,” the MacArthur center wrote in the suit.

Ethics experts and defense attorneys say the fake subpoenas were unethical and possibly illegal. Cannizzaro has acknowledged they were improper, but a spokesman told The Lens that they looked so formal because some people would just ignore a letter asking them to talk to prosecutors.

“We asked for these subpoenas two years ago and no one could find them,” the center wrote in the complaint. “Now we learn that there has been a serious abuse of authority related to exactly the subpoenas we sought, and that the DA is in fact the only person that would have legal possession of them.”

Jefferson Parish DA Paul Connick and North Shore DA Warren Montgomery admitted their offices used similar documents. All three DAs quickly announced they had discontinued the practice.

The suit quotes a New Orleans Advocate story in which an Orleans Parish prosecutor said he didn’t know how often fake subpoenas went out because the office didn’t have a formal recordkeeping system.

That’s a violation of the state public records law, MacArthur contends. It argues that the office “intentionally obfuscated” the true location of the records.

“It is now clear that Article 66 subpoenas — fraudulent and real — were not maintained as legally required. No one can locate them. If they cannot be found, they have not been legally preserved,” it says.

State law requires most public bodies to retain their records for at least three years.

The lawsuit also questions the constitutionality of Article 66 subpoenas, which prosecutors have used for obtaining documents and physical evidence, as well as witness interviews.

It says the law requires a lower standard to get these subpoenas — real ones, at least — than search warrants, which violates the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unlawful search and seizure.